When a streaming service like Netflix uses data analytics to recommend shows based on your viewing habits and demographic profile, it’s called smart business. By analyzing trends by age, region, and interest, they boost engagement and subscriptions. This kind of targeting is celebrated as innovation.

But when a public health department or nonprofit uses similar strategies—analyzing where vaccination rates are low or social needs are high to tailor outreach—it’s often met with accusations of “special treatment” or “unfair resource allocation.”

In both cases, the approach is the same: use data to identify need, then direct resources where they will have the most impact. So why do we applaud this strategy in business, but question it in public service?

This contradiction reflects a deeper issue: we have inconsistent standards for how data is used depending on who benefits. When profit is the goal, we call it efficiency. When people are the goal, we call it politics.

Just as companies market products to diverse audiences—young, old, male, female, trans, Hispanic, White—in the social sector we must understand who is most in need and how to best help them. Data helps us identify gaps, tell the story clearly, and shape better responses.

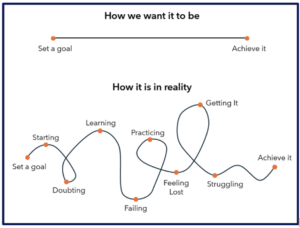

The social and public sector work with purpose. Instead of talking about profits, we talk about impact. For example, if efforts to address disparities leads to more women being screened for breast cancer, that’s a win. Not only are more lives saved, but families avoid the physical, emotional, and financial toll of late-stage diagnosis. The public also benefits from reduced healthcare costs. These are real returns—measured in lives, not just dollars.

Targeting help where it’s needed doesn’t mean taking it away from others. It means focusing on the root causes of why outcomes are not the same and helps build better systems that are more efficient and better for everyone. Providing food or housing support to people who don’t need it would be wasteful. Directing those resources to those who do is wisdom—not “wokeness.”

We need to be clear and confident when we present data to policymakers. Data is a tool for fairness, for solving problems, for building a healthier, more just society. And using it wisely should be something we all stand behind.