A very wise woman (Laura Pinsoneault) once told me that evaluation is simply a way of thinking, and by that logic, is something anyone can do. While there is extraordinary benefit to working with experienced evaluators for complex projects, anyone can use principles of evaluation in their daily life. In fact, many do so without realizing that is what they are they doing. My colleague, Bridgid Chanen, recently described how she uses evaluation tools to improve her rugby skills, for example. At its core, evaluation is a process of thinking about what you are doing, reflecting on what happened, and using what you learn to inform what you do going forward. Add some intentionality and the right tools for support, and this process becomes a very useful strategy to solve problems and achieve success.

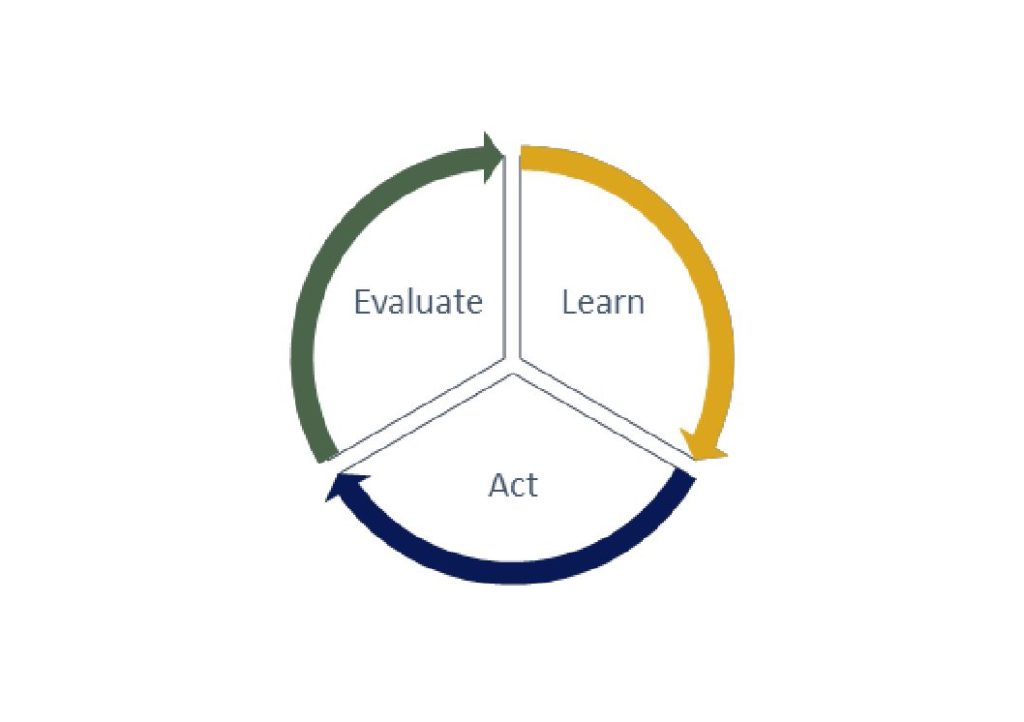

At Evaluation Plus, we specialize in developmental evaluation (DE)- which is a responsive and adaptable way of applying evaluative thinking. In essence, DE is a process for learning and a tool for innovation. Developmental evaluation is guided by a learning agenda which is used to rapidly test solutions and adapt actions based on data. The DE cycle in its simplest form looks a bit like this:

Growing My First Gardens

It’s no coincidence that my maiden name is Gardner. I am a gardener in every sense of the word. Every spring, I excitedly walk around my yard to see which new plants have sprouted, what flowers are about to bloom, and where I need to spend more time weeding. Each new development tells me something about the hours of work I put in last year, issues I may need to pay close attention to in the coming months, and how plants are responding to the weather, which – let’s face it – I have absolutely no control over. But, I was not always so astute.

Learn and Act

When I first started gardening, I lived in a duplex in the city, so my gardens were small. I had a thin strip of yard where I planted tulips and daffodils and a vegetable garden on top of a narrow retaining wall in the back yard. I remember thinking it was all relatively easy. After a few hours of hard work, I just sat back and let my gardens do their thing. The bulbs I planted in the fall emerged as beautiful flowers in the spring. With a little sunshine and rain, the vegetable plants rewarded me with a bounty of tomatoes, cucumbers, sugar snap peas, and peppers. With a few years of successful gardening under my belt, I was convinced I was a master gardener.

Now I know it was mostly beginner’s luck.

Several years ago, I moved to a new home with a big yard that was a blank canvas. Thanks to plant donations from my mom and grandma, my flower beds quadrupled in size. The perennial plants gifted to me were native to my area and low maintenance, so I focused my attention on the vegetable garden, which was three times larger than the retaining wall garden at my last home. A bigger garden meant a lot more work, and I wanted to ensure a plentiful harvest for my efforts. While I had already been experimenting, I still had a lot to learn—I had not only changed contexts but scale. I decided to document everything I did so I wouldn’t have to rely on memory for future reference. As it turns out, documenting my gardening experience became a useful tool for determining how to improve it. Like any developmental evaluation cycle, the information I wrote down served as data that informed my decisions and allowed me to adapt my plans to achieve greater success.

Act and Evaluate

The first tool I created was a planting map. At first it was just about making sure each vegetable plant had enough space and grouping plants that grew well together, known as companion planting. These maps helped me keep track of what I’d planted in past years, which plants needed more or less space, and what did well or poorly. After a couple years, this data helped me identify the vegetables that continuously grew best. Tomatoes, peppers, and herbs thrived in my garden! I wanted to grow more varieties of those things, but they were hard to find at my local garden center. As a result, I decided to start growing all my veggies from seeds, which opened the door to many more varieties. Suddenly, there was a new set of variables in the mix.

I was going in the right direction, but the scale and scope of my project was changing. To keep track of the whole operation, I needed new tools to help me learn and my garden grow. Spreadsheets helped me track basic gardening data – how deep to plant different seeds, how many days to germination, and when vegetables would be ready for harvest. As the years went on, I added other data that I found to be helpful, such as the dates to start specific seeds indoors, when to transplant seedlings outside, and which seeds do better when sown directly outdoors versus started inside. Some of this data was informed by research I did in preparation for each new growing season (evidence-based learning). Other data points I discovered through experience (evidence-building learning). Different methodologies helped me identify the supplies I needed and build an inventory: grow lights, extension cords, seed starter pots and soil, plant markers, and seed packets. I also started using a notebook for observational data. Each season I track the varieties and sources of seeds, write notes about how plants performed, document diseases or pests I encountered and how I treated them, and so on. Together these tools helped me identify patterns, point to successes, and quickly let me learn about problems. This kept my garden strong and healthy.

What I Learned from My Gardening Experience

The conditions we garden in are always changing. A healthy garden requires testing and acting in near real time, or you will lose an entire growing season. Developmental evaluation is designed for this type of learning and growth.

Evaluation has become an essential part of my gardening. Each February, I review my maps, reflect on what worked or needs to be changed, and use that information to make decisions about the plants I will grow in the coming year. I make plans, take stock of supplies, and generally feel hopeful that the snow will melt and the sun will shine. But evaluation does not stop there. The habit of systemizing what I am learning each week of the growing season brings new and unexpected changes. While my harvest fluctuates from year to year, my knowledge always grows. Like any learning process, developmental evaluation is constant, and with the right guidance and tools, can make change possible.

Using tools like maps, spreadsheets, written notes, observation, and a habit of intentional reflection, I can make decisions to alter course. I can solve problems and prevent new ones. And if you think like an evaluator, you can too.