When I started working at Evaluation Plus, I did not know a lot about evaluation. Over the last couple of months, I have learned a lot about what evaluation is and how it is useful. However, I know that evaluation can seem confusing and difficult at first. It is easy to look at more complex systems-level evaluation and forget that aspects of evaluation happen in our daily lives whether we know it or not. In fact, evaluation is used in areas as far from the business world as the high school rugby field. As I learn more about evaluation, I find that many of the tools I use in my daily life to grow as a rugby player are the same tools used by evaluators to help solve large-scale problems.

A Theory of Change

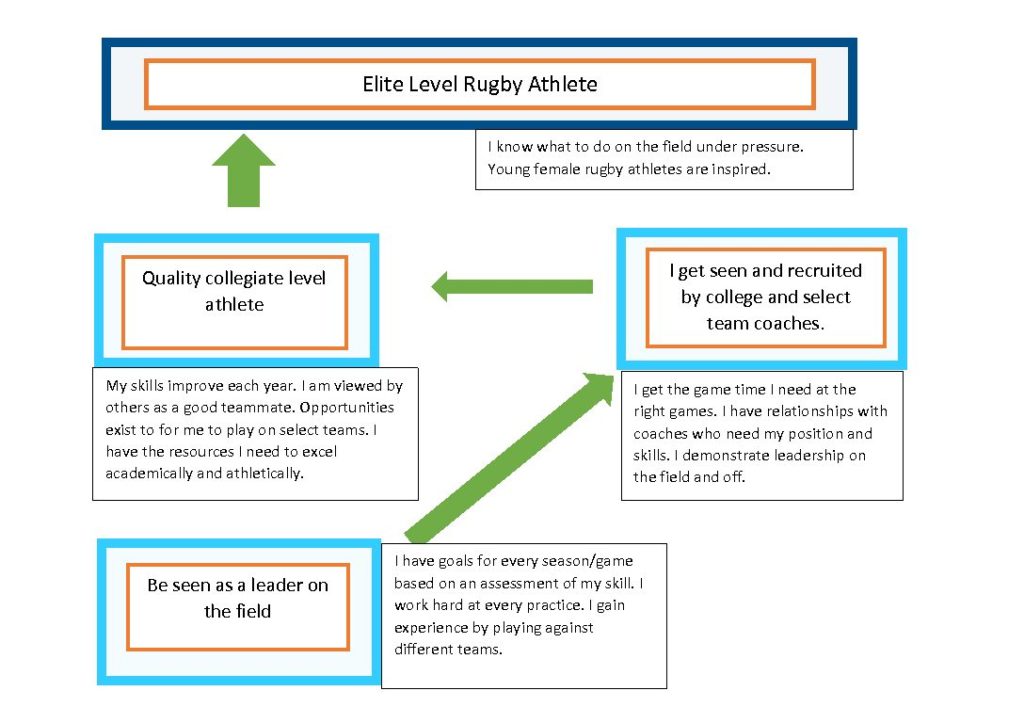

One of the first tools I learned about at Evaluation Plus is a theory of change. A theory of change is a tool for problem solvers to map out all the conditions that need to change to get a result. The work of building a theory of change can feel overwhelming, but as it turns out many of us are already building our theory of change without even knowing.

Make the change possible: What motivates me to improve as a player is my long-term goal of playing rugby at an elite (“professional”) level. When I think about this goal, I can paint a detailed picture in my head of how I will play at that level. I’ll be able to lift a certain weight, sprint at a certain speed, communicate consistently on the field, have excellent tackling technique, etc. The change I wanted to create was a significant improvement in my rugby skills. For a social problem solver, there may be more complex pieces involved, but the question is still the same—what would it look like and feel like if the change is possible?

Know the needs and priorities to sketch a path that makes sense. Even when two people or organizations think they are working towards the same end, it may make sense to take different routes. For example, in rugby there are two different groups of players called backs and forwards that typically have different roles in a game, so even though they are both trying to win the game a back may need to concentrate on building speed and passing ability to contribute to their team’s victory and forwards may want to focus more on strength training and running through contact. A needs assessment is a way of finding what changes need to be made, where they need to be made, by who, and what tools and resources are at your disposal to make that possible. For social problem solvers, needs assessments include a variety of techniques such as surveys or focus groups and should consider the perspectives and experiences of many people from a diverse array of backgrounds. In my small-scale example, my needs assessment was conferencing with my coaches, asking older players for advice, reviewing game film, looking at where the sport is headed, etc. This process allowed me to assess what skills I had, what skills I needed to develop, how I compared to others who were doing what I wanted to do, and figure out all the different resources and people that might be involved in or have a stake in reaching “the vision”. I could then map out what I needed to achieve each step on the path towards my “vision” (this is what evaluators call “conditions of change” or outcomes.)

If my theory of change were written on paper it would look something like this:

Learning as I go

Of course, this process is not nearly this linear and organized. A theory of change helped me think about where I was going but I still had to figure out how to get there. This is where short-term goals come in. For social problem solvers, this is where your evaluator may be asking which levers you are going to pull with your current strategies.

Initially I set short-term goals based on what my coaches told me to do or what I thought they think is success. For example, my goals would be vague like, “be a better ball carrier” or “make more lower tackles” and they would sit on a notecard to be forgotten by my end of season review Looking back on these goals, I was not getting very far, and I started to wonder why. It was here that I learned a few things about goals and learning along the way.

First, YOUR goals should fit where YOU are at. My coaches’ goals for our team were designed to be as general as possible. I had my own unique strengths and my own unique needs to consider. I was honing skills I hardly used in my position. I needed to become great at the skills I know I will get seen doing.

Second, goals need to be specific, measurable, and FEASIBLE. I needed to set my goals to a scale appropriate for what I was doing. I needed my goals to make sense for rugby. For example, one of my goals was to make three great tackles every game. While three sounds like a really low number to most, after years of playing rugby, I knew that I could make 10 tackles in a game, but three low, driving, quick tackles would be hard to achieve. My needs assessment helped me set the right benchmark, not just a benchmark.

Third, goals should evolve and adapt. Before I had my roadmap, I was working on all my goals at once. I was setting so many goals that there was no way I could achieve any of them. Once I recognized that reaching a vision was about making progress over time, I was able to choose a couple of goals to work on at a time as logical steps towards success. In my junior year, I set 2-3 logical, specific goals per a game and I managed to achieve all of them. This shows that evaluation is not only something we do in our daily lives, but something that can lead to real change and problem-solving.

While evaluation, like any skill, may be difficult at first, looking at it in a small-scale or familiar example can help you understand how to use it to solve complex problems. Additionally, these small-scale examples of evaluation remind us that we all use evaluation to solve problems, we just need tools to organize our thoughts when the problems we try to solve become more complex.

One Comment

Comments are closed.