By Kristen Gardner-Volle and Laura Pinsoneault

Basic science led to the discovery of antibodies in 1890. It was a cataclysmic moment in history, paving the way for breakthroughs and treatments of diseases. At its core, basic science is the foundation of scientific knowledge. Wouldn’t it be something if basic science could do for cancer disparities what it has accomplished for medicine?!

The truth is we will not know unless we try. We do know that certain groups are at higher risk of developing or dying from cancer. Why? What is going on and what can we do about it? Basic scientists can help provide answers. They are naturally intrigued by figuring out how things work, and it’s that kind of inquiry that can lead to the answers we need to save more people from cancer.

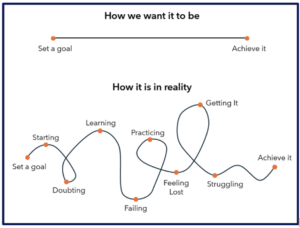

Our interviews with basic scientists reveal that serendipity plays a role in how they came to study certain questions. It could be an influential mentor, research funding that came through or certain collaborations that developed. But what if we created an environment where the conditions existed to encourage basic scientists be part of cancer disparities research? We could then create the serendipity and encourage incorporation of a community orientation, or a focus on disparities, systems, deep equity and social determinants of health – factors that are not often considered in traditional basic science.

We need to initiate the opportunities where they don’t already exist. For example, funders can apportion grant programs in this area, requiring that cancer disparities research include basic scientists so community needs are factored into their studies. This could include high-risk, high-reward funding for investigators willing to incorporate hard-to study variables in their research design.

Let’s also encourage research-based institutions to join the party. Universities and academic medical institutions can provide education and training for basic scientists to learn the skills and strategies necessary to effectively engage in cancer disparities research, collaborations and initiatives. This can help build the knowledge around biologic, social and systemic factors that lead to cancer disparities.

It’s also imperative for individual researchers to integrate a community orientation in their work. They can prioritize transdisciplinary opportunities to learn from others outside their sphere or specialty. Their commitment to equity, inclusion and diversity in science will help foster these very things in their research.

When these efforts begin to happen, we will then see new areas to explore and unexpected collaborations. This is just the sort of environment that can lead to discoveries akin to the antibodies revelation, where a whole new world opens and breakthroughs are realized.

Kristen Gardner-Volle, MS, is a Research & Evaluation Associate at Evaluation Plus. Laura Pinsoneault, PhD, is the company President and CEO.